Contributed by Zane Hood, Principal, PPM Consultants

Contributed by Zane Hood, Principal, PPM Consultants

A few weeks ago, Todd Perry and I hosted a PPM Simplifies podcast discussing the evolution of gasoline and octane additives. We talked about how almost all the gasoline in the retail marketplace now consists of 10% ethanol. We noted that ethanol is much more expensive to refine, which raises the question: why would the free market suddenly include 10% ethanol in gasoline? Ethanol boosts the octane of fuel but comes at a high financial cost. Not only is it expensive to refine, but it also potentially causes corrosion or scouring of equipment components if those materials are not compatible.

Ethanol is “hygroscopic,” meaning it tends to absorb water from its surroundings. When ethanol-blended fuels (like E10 or E85) absorb too much water, a process known as phase separation can occur. In this process, the absorbed water and ethanol mix separate from the gasoline, forming two distinct layers: an ethanol-water mixture at the bottom and gasoline at the top. This can lead to engine problems, especially in vehicles, as the ethanol-water layer may not burn efficiently. Additionally, the presence of water in fuel systems can promote corrosion in metal parts like fuel tanks and fuel lines, potentially creating millions—if not billions—of dollars in cleanup costs due to leaking UST systems.

Take a simple example of small engines in home lawn equipment. Personally, I only use ethanol-free fuel in my lawn equipment, and it runs flawlessly compared to the problems I encountered when using ethanol-blended fuel. When I fill up my 5-gallon container with ethanol-free gasoline at my neighborhood gas station, I pay a premium for it! Despite being cheaper to refine, ethanol-free fuel is much more expensive at the retail dispenser simply because supply is low, and demand is high. This all seems illogical, except when you consider government subsidies—or some might call it intervention.

As mentioned earlier, refining ethanol is significantly more expensive than producing traditional gasoline, primarily due to the nature of the raw materials, energy-intensive processes, and infrastructure required. While gasoline refining costs range between $0.40 and $0.70 per gallon, ethanol costs typically hover between $1.00 and $1.50 per gallon, depending on fluctuating corn prices and other market conditions. Despite this cost differential, the U.S. government has encouraged the use of ethanol and other renewable fuels, largely through the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which established the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). This landmark legislation made ethanol a vital component of the nation’s fuel strategy, and the Renewable Identification Number (RIN) program is one of the primary mechanisms supporting this shift. The government effectively subsidizes ethanol refining through this system, pushing the marketplace toward more renewable fuels.

The process of turning corn into ethanol is labor-intensive and resource heavy. Corn, the primary feedstock for ethanol in the U.S., is subject to volatile agricultural pricing, and the refining process requires significant amounts of heat and energy for fermentation and distillation. Even with technological improvements, ethanol remains more expensive to produce than gasoline on a per-gallon basis.

Furthermore, ethanol has a lower energy density than gasoline, meaning vehicles need more ethanol to travel the same distance, increasing the effective cost of using ethanol in transportation. Without government subsidies—or intervention, depending on how you look at it—ethanol’s high production costs and lower energy content would make it an unattractive option in the marketplace, especially when compared to gasoline derived from crude oil, which benefits from decades of industrial optimization and infrastructure investment.

Government Intervention: Subsidies and the RIN Program

To reduce carbon emissions and decrease dependence on fossil fuels, the government has implemented a series of incentives to make ethanol and other renewable fuels more competitive. One of the most impactful tools in this effort is the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), which mandates that a certain percentage of renewable fuel be blended into the nation’s fuel supply each year. The RIN program plays a central role in this system.

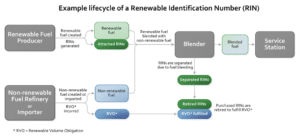

Under the RIN system, renewable fuel producers “generate RINs” when they produce ethanol or other biofuels. These RINs can then be traded, separated from the physical fuel once blended, and used by obligated parties—such as refiners and importers—to meet their annual renewable fuel quotas. This creates a secondary market where obligated parties that blend more renewable fuels than required can sell their excess RINs to those needing them, creating a financial incentive to produce and use more renewable fuels. Below is an example of the lifecycle of a RIN:

The RIN program is a critical tool pressing the marketplace toward renewable fuels like ethanol. Through the RIN trading system, the government effectively offsets some of the costs of producing and refining biofuels, leveling the playing field between expensive renewable fuels and cheaper, fossil-based alternatives like gasoline. As RINs can be traded, they effectively assign a price to compliance, and the cost of RINs fluctuates based on supply and demand dynamics.

When the supply of renewable fuels is low or demand for RINs is high, RIN prices rise, incentivizing more biofuel production and blending. Conversely, when biofuel production is high, RIN prices drop, encouraging greater use of renewable fuels. In this way, the RIN system aligns market incentives with the government’s policy objectives, using market mechanisms to push obligated parties toward renewable fuel usage—even in the face of higher refining costs.

Thanks to the RIN program and other government subsidies, ethanol has become essential to the U.S. fuel mix. Even though ethanol is more expensive to refine, these policy tools ensure that biofuels remain competitive. Without government support, the higher cost of producing ethanol—due to its complex refining process and reliance on agricultural commodities—would likely result in much lower adoption rates, if not a complete collapse of its economic viability.

Though driven by government subsidies, you can probably see how the RIN process also includes a strong element of free-market capitalism. The government’s desire to reduce the use of fossil fuels has birthed an entire market. I’m sure corn growers love it, which is one reason their lobbying efforts strongly supported George W. Bush’s Energy Bill of 2005!

I would love to hear your thoughts on this. Feel free to reach out to me at zane.hood@ppmco.com.